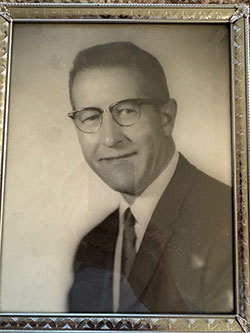

John Neupert built a blue-collar life for his family as a milkman, bread delivery driver, and in insurance sales. But a years-long battle with heart disease and heart failure beginning in the 1960s eventually took his life in 1973 at age 57.

At the time, treatment options were limited and, after a series of heart attacks, doctors considered what was then a new procedure: open heart bypass graft surgery. But Neupert’s left ventricle was too damaged to proceed.

The determination with which he faced and survived multiple heart attacks left a deep and lasting impression on his son, Jim. His father’s struggle and eventual death sparked his son to explore a career in finding solutions for heart disease and identify new treatments to help spare other families the tragedy the Neuperts endured.

“My dad knew he didn’t have a chance to recover and have a normal life,” says Jim, who grew up in Monona, a small city bordering Madison. “He just hoped the doctors would learn something about his condition that would be helpful to others and to how treating heart disease might be advanced in the future.”

John Neupert died while Jim and his brother were attending the University of Wisconsin–Madison as undergraduates.

John’s wife, Caroline, went back to work to help make ends meet. The brothers worked their way through school, earning a combined five degrees. Jim earned a bachelor’s in business and an MBA, while Richard earned a bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate and went on to become a professor of film studies at the University of Georgia.

“We worked summers, weekends, and nights so we could pay for 100% of our tuition and cost of living,” Jim says.

Jim applied his business expertise in the medical technology industry in marketing, sales, and business development at Edwards Labs, Eli Lilly’s Medical Devices Division, and Guidant. Most of his work over some 30 years centered on implantable cardiovascular devices, such as implantable defibrillators and coronary stents.

In his role, Jim worked with top researchers, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and other specialists globally to improve patient outcomes. As a business development leader in the industry, he helped identify new technologies and anticipate what the future of cardiovascular treatment would look like.

“I thought a lot about my about my dad’s journey in heart failure, and what his life and the life of my mom, my brother and I would have looked like if more advanced technology had been available 20 years earlier,” Neupert says. “I’m convinced he would have lived another five to 10 year and seen Richard and I graduate from the UW if more advanced solutions had been available in his era.”

“With this research chair, my dad’s memory and his personality traits of determination and optimism will be walking through the front door of the Morgridge Institute for Research for many decades to come.” Jim Neupert

Now retired in Atherton, Calif., Neupert continues his keen interest in advancing solutions for heart disease by supporting leading-edge research at the Morgridge. In 2024, Jim’s gift established the James W. Neupert Investigator in Regenerative Biology, to support the research of Ken Poss, Morgridge’s director of regenerative biology.

Poss investigates fundamental rules of organ regeneration in zebrafish, which raises exciting questions about whether similar capabilities could one day be unlocked in humans to repair heart and spinal cord damage.

“This is maybe one of those things out there in the future — that my dad was hoping would show up,” Jim says. “It’s part of his timeline. I look at it as part of his life, part of his journey.”

Jim is an enthusiastic supporter of scientific research and has also made gifts to support Morgridge’s Summer Science Camps, an immersive program for high school students and teachers in rural communities and from historically underrepresented groups in science.

He is also a passionate UW–Madison supporter. He served for 20 years on an advisory board for the School of Business MBA program and established a scholarship named for his mother, which supports underrepresented, low-income university students.

“The UW had a major impact on how my brother and I defined our futures,” says Jim. “It prepared us for the fields we entered after graduation.”

Being able to support research that could lead to new treatments to treat heart disease gives Jim a special sense of satisfaction.

“With this research chair, my dad’s memory and his personality traits of determination and optimism will be walking through the front door of the Morgridge Institute for Research for many decades to come. I’m sure he’d be honored to be remembered as these scientific breakthroughs are made.”