As spectacular as modern imaging can be in illuminating the tiniest aspects of life, some avenues of biology are still cloaked in darkness.

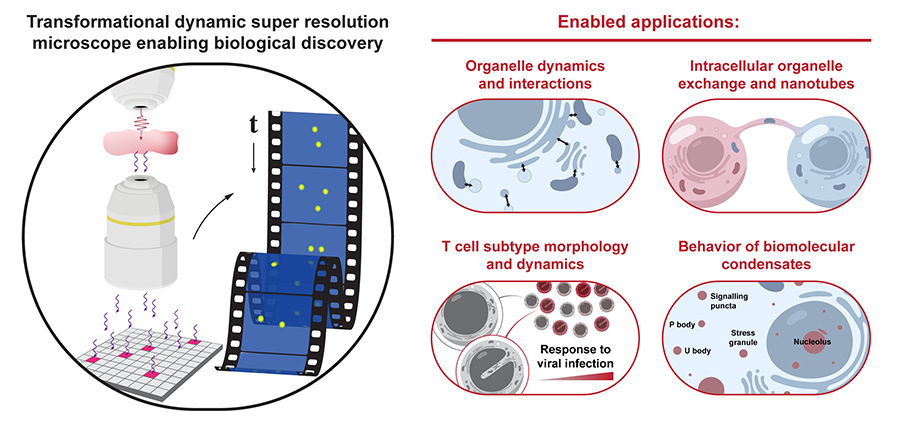

Biological processes that happen over long periods of time — for example, exchanges of materials between cells — are hard to capture with conventional microscopy. Likewise, processes that occur quickly, such as interactions between organelles, lack sufficient resolution for researchers.

A team of physicists-by-training has a novel strategy for breaking through this roadblock: Merge modern light microscopy with the rules of quantum physics, to usher in a new era of super-resolution imaging that can aid in diagnosing and treating disease.

Scientists led by the Morgridge Institute for Research, Colorado State University and the Colorado School of Mines have teamed together on a multi-year project to build a new generation of microscopes that marry both classical and quantum measurements. The project received support in December from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, an organization that works to advance knowledge through pioneering technological advances.

“Quantum” is a having a major moment in the world of computing, where scientists are actively pursuing ways to harness rules of quantum mechanics to make computers many times faster than today’s technology. But how would quantum physics relate to how we view the biological world?

Randy Bartels, a Morgridge biomedical engineer and lead investigator, says current approaches to super-resolution imaging rely on fluorescent labeling, where biomolecules of interest are “tagged” by fluorescent molecules that can be detected by microscopes. But these elements only produce light for very short periods before vanishing, limiting their ability to capture dynamic features. The fluorescence process can also disrupt or alter the biology taking place.

Quantum optics allows researchers to exploit properties of light that are not seen by normal cameras, making greater use of natural rules that already exist. Bartels says quantum approaches will be based on more universal properties of light and photon statistics that are invisible to classical measurements. The new microscope will capture more information than current microscopy technology, information used to unveil hidden information in cells.

“We believe that the ability to measure the quantum behavior of light, beyond the conventional strategies open to classical imaging, will create a critical path to advancing super-resolution imaging and open a new window into the nanoscale universe,” says Bartels.

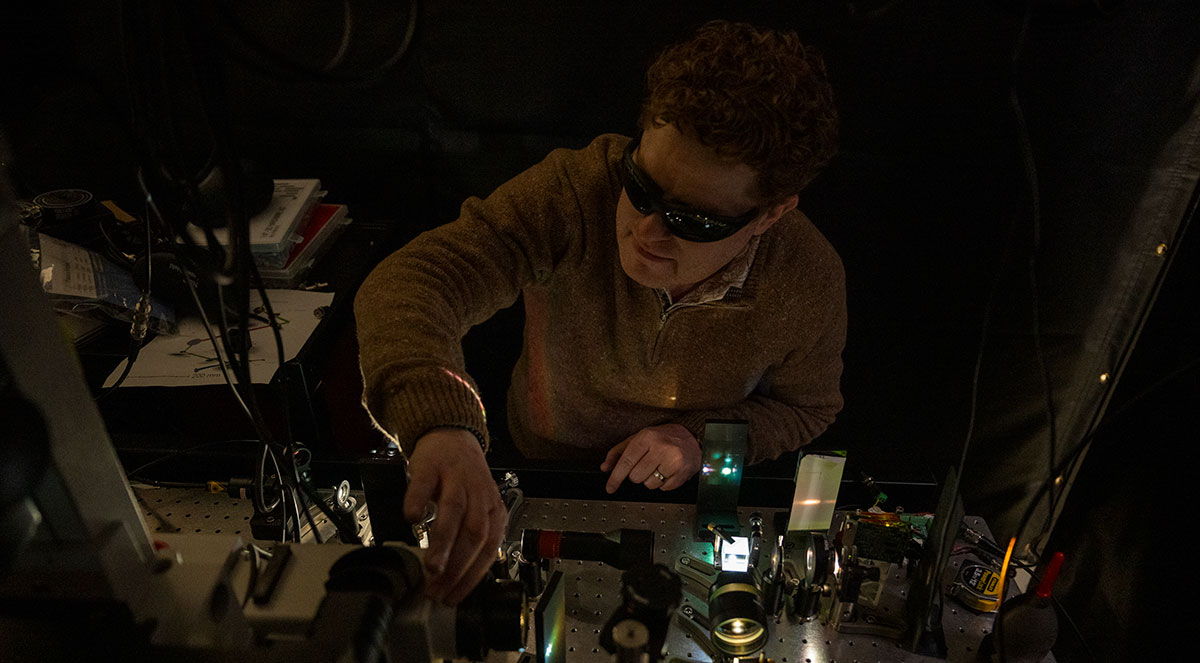

Co-investigators on the project include Jeff Squier, physics professor at the Colorado School of Mines; and Olivier Pinaud, professor of mathematics at Colorado State University. Squier has worked extensively on establishing single-element detection imaging technologies with applications from advanced manufacturing to the biological sciences. He pioneered Third Harmonic Generation (THG) microscopy with application to biological imaging; a key component of this new research program. Pinaud is an expert in the mathematics of quantum mechanics and quantum optics and had contributions including the theoretical analysis of partial differential equations in the context of wave propagation and quantum physics.

In the first phase of the project, the team will continue basic research on the nature of quantum optics and photon statistics, to determine how these principles can be incorporated into microscopy. This includes understanding the physics of how photons are distributed through coherent nonlinear scattering — a process where strong light passes through a material and generates greater light frequency. They will exploit quantum correlations and improve the spatial resolution and speed of microscopy over classic coherent nonlinear imaging approaches.

Once the microscope is built, the researchers will conduct imaging experiments to understand intricate biological dynamics of nanoscopic structures that stand to gain the most from this new quantum approach. This includes research on tiny structures inside our cells, known as organelles, to understand how their movements and interactions directly influence our overall health.

Other possible imaging targets include investigating tiny bridges called nanotubes that cells use to swap materials, especially since cancer cells can cleverly use these bridges to disable the immune system’s T cells. “To fight back, we need to improve immune therapies, which requires using advanced microscopes to watch T cells change shape and move in real time without damaging them,” Bartels says.

These improved imaging tools will also be deployed to help improve understanding of structures called biomolecular condensates, which act like liquid droplets to organize vital tasks such as how the cell responds to stress.

“Our goal is to apply this new microscope to study aspects of biology and biomedical research that cannot be observed with current imaging technology. Our aim is to open a new world of observations into intercellular and subcellular dynamics,” says Bartels. “Understanding these dynamics is the foundation to analyzing the mechanisms at play in health and disease as well as designing and manufacturing treatments.”