Science drives a transcontinental path back to Madison

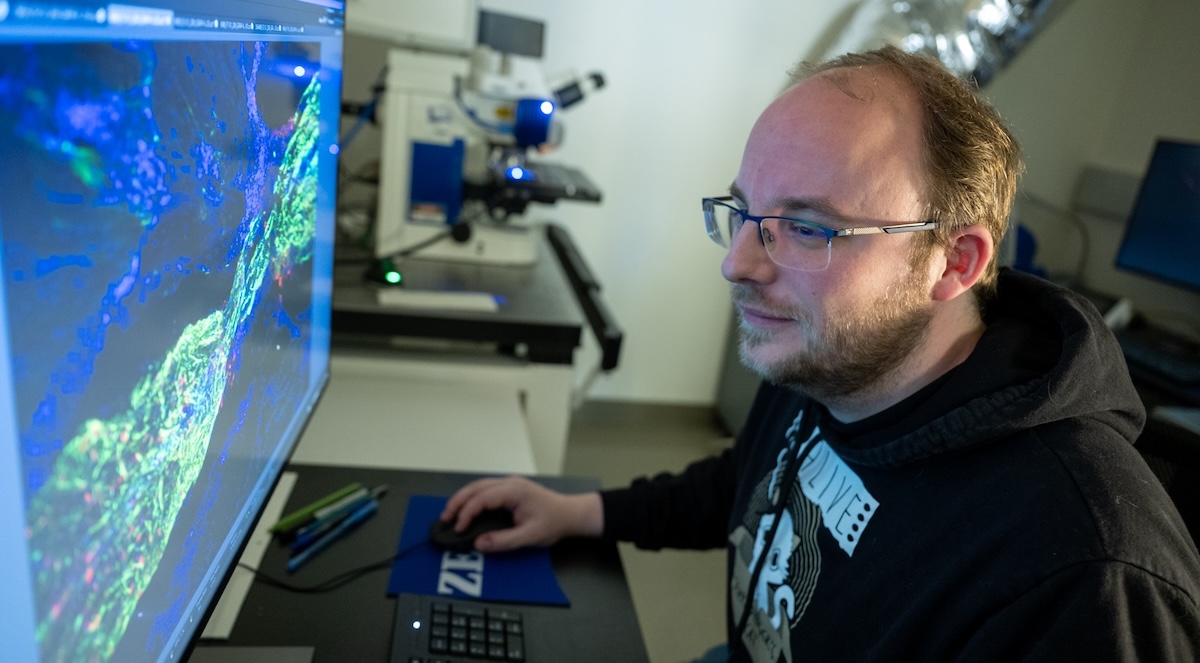

Pierre Gillotay’s transatlantic journey to Madison began by coincidence seven years ago at the Memorial Union, just blocks away from the Morgridge Institute for Research.

Gillotay’s first visit to Madison came in 2018, when he attended a conference on biomedical research using zebrafish. Between sessions, he’d sneak out to the Terrace periodically to watch World Cup soccer matches on a big-screen TV.

But even more captivating for Gillotay — then a doctoral student at Université Libre de Bruxelles in his native Belgium — was a presentation by a postdoctoral scholar in the Duke University laboratory of regenerative biology pioneer Ken Poss.

He was so fascinated by the presentation, which focused on using DNA from the fish to trigger cell proliferation in mice, that when he finished his PhD Gillotay contacted Poss to inquire about joining his Duke University lab.

“I was very stressed to contact him,” he recalls. “And I got a response about five minutes later. But it was an automated out-of-office message. That day was an emotional rollercoaster.”

But the two managed to connect and in 2022, Gillotay joined the Poss Lab. And when Poss last year accepted an offer to became director and James W. Neupert Investigator in Regenerative Biology at Morgridge, Gillotay completed the circle by moving to Madison to continue his research.

The Poss Lab studies the cellular and molecular mechanism of innate regeneration in model systems like zebrafish, known for their ability to regenerate injured tissues. It hopes to use those examples to improve the poor regenerative capacity of human tissues such as the heart, spinal cord, and limbs.

“My current project focuses on adult zebrafish and how their ability to regenerate tissues could affect spinal cord regeneration,” says Gillotay. “There is a proportion of the fish that do not show a perfect regenerative outcome and remain paralyzed. If we know what’s failing in those cases and can rescue it, maybe we could trigger a non-regenerative animal to get to the point of regeneration.”

There are few scientists conducting research along the same lines.

“That’s a good thing,” Gillotay says. “You have a little more freedom to explore more risky options. There’s not the constant pressure of ‘I need to be fast, otherwise I’m going to get scooped,’ because there are 100 others doing the same work.”

Gillotay arrived at Morgridge in the fall of 2024 but quickly sensed a scientific culture that encourages curiosity and collaboration.

“There is a wide range of work being done here that is stimulating as much in the technical realm as in the conceptual one.”

Pierre Gillotay

“It is stimulating. It’s very chill and welcoming,” he says. “There is a wide range of work being done here that is stimulating as much in the technical realm as in the conceptual one.”

Gillotay grew up in Brussels, the son of two chemists — a father who works in a government lab studying the physics of high-atmosphere chemical reactions and a mother who works at the university in the nuclear waste management department.

“We were always on the university campus growing up. It was a kind of playground,” he says. “I was never really pushed toward science, but that’s what we grew up surrounded with. My parents always gave us the freedom to do what we wanted to do.”

As a doctoral student, Gillotay credits his mentor, Sabine Costagliola, for deepening his scientific rigor and providing him an academic role model. His doctoral work involved using CRISPR to identify factors important in thyroid development and functional maturation in zebrafish.

“She was extremely talented at fostering people’s curiosity and independence,” he says. “She was extremely fair but still demanding. And she put a lot of effort into providing a working environment that people enjoyed.”

Gillotay is eyeing an academic future as a principal investigator.

“I was lucky enough to see the very encouraging aspects of what PI life can be through my graduate mentor. I want to give that chance I had to other people by opening a lab, and show that you can be humane, you can do good science, and still make people enjoy it,” he adds.

Rising Sparks: Early Career Stars

Rising Sparks is a monthly profile series exploring the personal inspirations and professional goals of early-career scientists at the Morgridge Institute.