Scientists at the Morgridge Institute for Research are raising the ante on the common phrase, “Every picture tells a story.”

The research team has developed a database that combines 2.8 million cellular images — captured across a wide range of imaging modalities — which can be used to train machine learning models to help answer questions about basic biology, functional genomics, and treatment design.

Morgridge investigator Juan Caicedo says the ultimate goal is to provide researchers with a more universal tool to examine cellular morphology for biological studies. Cell morphology involves analyzing the size, shape, structure and patterns of cells to better define the differences between healthy and diseased states. Using machine learning, these tools have proven to be a very powerful way to study how cells respond to treatments, among other biological applications.

The problem today, Caicedo says, is the models in use are highly specialized. They can, for example, quantify liver cell images from confocal microscopy, but would not be able to recognize the same cells coming from fluorescence or electron microscopy.

Caicedo and his team are gunning for a “one size fits all” model.

“If you look at how artificial intelligence is applied to microscopy today, most of these models are trained on one specific type of microscopy image,” says Caicedo, also an assistant professor of biostatistics at UW–Madison. “So we started to realize that if we really wanted to make progress, we need to create models that can be more broadly applicable for scientists.”

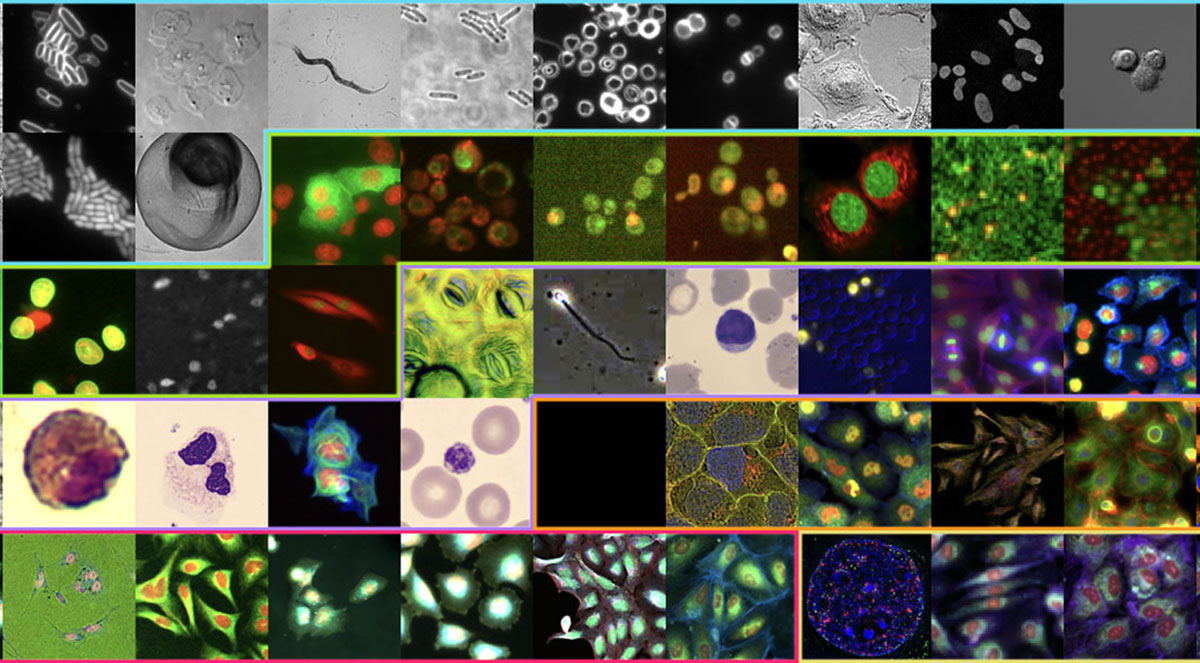

The database, made publicly available to researchers in early 2026, is called CHAMMI-75, which stands for “channel-adaptive models for microscopic imaging.” The number 75 represents the different data sources of cellular images that are included in the database.

All told, the model collects images of more than 1.8 billion cells, which have been standardized through common formatting and metadata, essentially getting them to “speak the same language” even as they are derived from vastly different sources. The site includes images from 14 different imaging modalities, such as fluorescence, confocal, cryo-electron, or other “flavors” of microscopy. And it incorporates images across 16 different organisms and 15 different magnification levels.

“Every microscopy lab needs this type of capability, there is a real need, and we believe that our approach can help them.” Juan Caicedo

The concept of “universal morphology” actually takes a cue from early successes in large language models (LLMs), Caicedo says. About a decade ago, AI researchers began to develop LLMs that are trained across many different languages. Rather than having to create new AI platforms in each language, AI proved capable enough to analyze and find similarities across virtually all languages.

“I remember reading a paper where they made experiments with 100 languages at the same time for the first time, and the results were amazing,” Caicedo says. “The more languages you put in, the more fluent the model becomes, even when the language doesn’t produce a lot of data — imagine a very rare language.”

“It turns out that languages that have very few resources benefited the most from that joint modeling, because there are some commonalities in all human languages,” he adds. “If you specialize a model for this rare language, you are constrained to only the few documents that you have for that language.”

Caicedo says he hopes CHAMMI-75 can provide the same kind of effect, where AI can apply some of those commonalities across all cells to shed light on rare or poorly understood diseases. After all, there are more than 200 cell types in the human body, and all have common elements such as DNA, nuclei, membranes, and organelles. There is bound to be evidence from well-studied disease states that can inform lesser-understood conditions, he says.

One of the immediate applications will be in drug development and repurposing, as a confirmation and prediction tool to help scientists choose the best direction when hundreds of different compounds are tested. It may also inform smarter forms of microscopy, that can be programmed to identify different phenotypes in real time, while experiments are being conducted.

Examples of some of the imaging data used in CHAMMI-75 include not just human-derived cells, but cells from other mammals, bacteria and even plants. It includes data from genetic screens, drug screens, 3D imaging and specialized cell biology. It includes public data from some of the world’s largest existing cell atlases, such as the Image Data Resource, the Human Protein Atlas, and the Cell Painting Consortium.

Several biology research labs have been using methodologies from the Caicedo lab on their own image collections. Morgridge investigator Ken Poss, for example, studies regeneration in zebrafish hearts, and their data helps show how heart activity evolves under certain genetic conditions. A team at Johns Hopkins University is using it for a database of human derived cell lines from schizophrenia patients, and a Copenhagen University team is using it to quantify micronuclei formation.

“We’re trying to find as many examples of image-based experiments as possible to enrich the quality of the measurements that we provide to real-world biological studies,” Caicedo says. “Every microscopy lab needs this type of capability, there is a real need, and we believe that our approach can help them.”