My college physics course introduced me to Newton’s third law of motion, which teaches that when you push a box across a mythical frictionless surface, the box is somewhat politely pushing you back. The idea stayed with me. It offered a simple way to understand how systems ebb and flow in response to various pressures: every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

Scientific research, I would later learn, behaves similarly, albeit with far more friction.

In the ecosystem of discovery, the “reaction” to a restrictive force isn’t always resistance. More often, it resembles resilience: the quiet strength of bending without shattering. When familiar support falls away and external pressures mount, scientists have found ways to reorganize and create new structures that keep knowledge moving forward.

This pattern is evident in two campus origin stories: the founding of the Morgridge Institute for Research in the early 2000s, and the creation of the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) a century earlier. Both institutions emerged during moments when scientific progress faced political or financial constraints, and both were built by Wisconsin researchers demonstrating how their communities adapt to preserve the momentum of discovery — a lesson that feels urgent amid today’s unstable funding landscape and eroding public trust.

In August 2001, a federal executive order limited funding for embryonic stem cell research. At the time, UW–Madison had become the epicenter of this field thanks to James Thomson’s groundbreaking discovery on how to isolate human embryonic stem cells in 1998. Navigating the complexities of federal support, Wisconsin scientists and advocates worked with philanthropic partners to build new research infrastructure, culminating in the founding of the Morgridge Institute for Research in 2006. This institutional response not only allowed stem cell research to continue but helped shape the emerging field of regenerative medicine.

This spirit of resilience goes back at least three generations. In the 1920s, university research was chronically underfunded and increasingly forced to compete with an expanding industrial research sector in a loosely regulated medical marketplace. When UW biochemist Harry Steenbock discovered how to fortify foods with vitamin D, a breakthrough that would help eliminate rickets worldwide, he chose not to sell the discovery for personal profit. Instead, Steenbock worked with university leaders to create what in 1925 became WARF: a nonprofit structure that would allow the university to steward its discoveries, manage patents responsibly, and reinvest revenue into future research. This model has persisted through depressions, political swings, and shifting scientific priorities for a century.

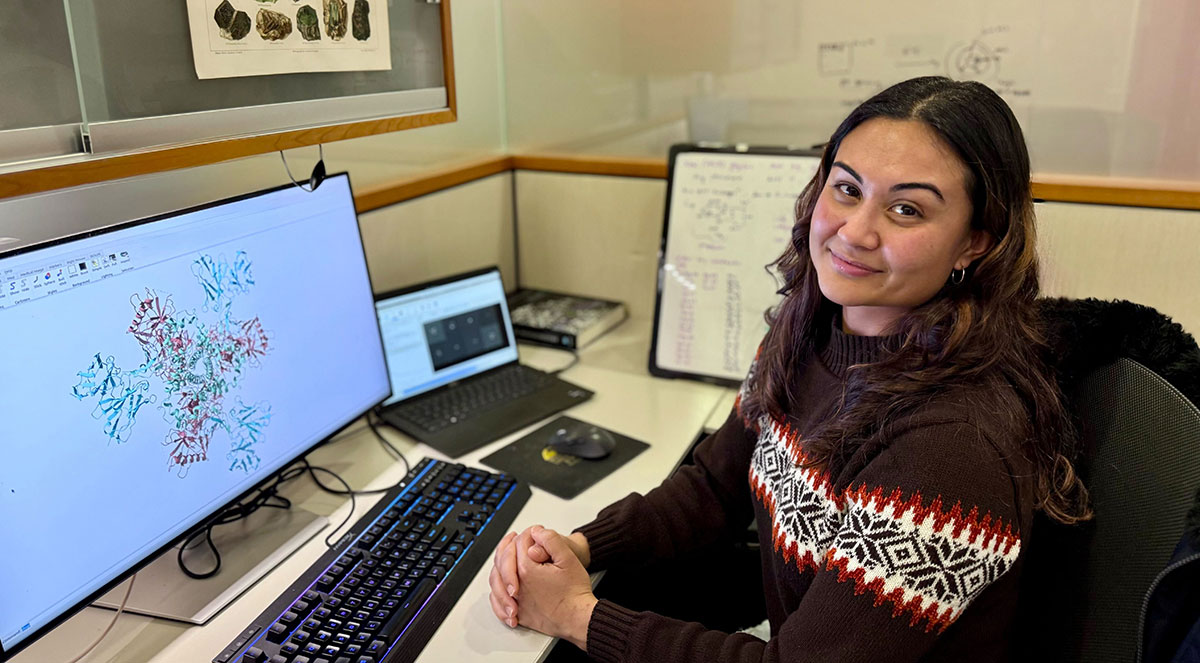

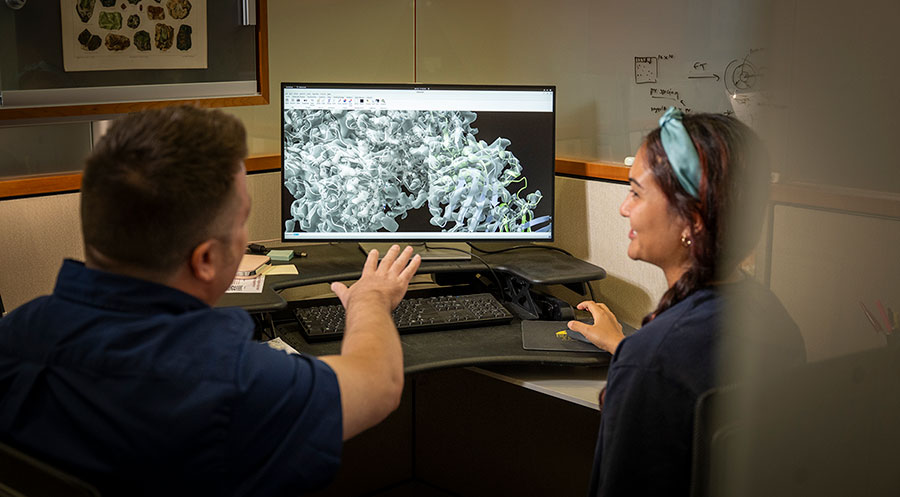

My own field, cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), is notoriously expensive and resource-intensive. The cryo-EM facilities at UW–Madison exist because of sustained investments in research infrastructure from the Department of Biochemistry, Morgridge, and WARF, along with major equipment grants. This collective support allows facilities like ours to function at the scale and precision modern research demands.

But while the successes of WARF and Morgridge might suggest that that institutional strength alone guarantees scientific progress, as a graduate researcher working across UW–Madison, Morgridge, and WARF, I’ve observed that resilience is not a static inheritance. It is something each generation must rebuild for itself.

I recently encountered such pressures while collaborating with scientists in South Africa to understand antibody responses to HIV. Federal restrictions on NIH funding, along with foreign policy cuts to South Africa, disrupted our project and other HIV/AIDS-focused work. Our research continues, but under ongoing uncertainty, while other research projects have stalled entirely. This fragility reminds us that discovery depends not just on producing rigorous data, but on constantly reinforcing the stability of the larger systems around it.

This is where the legacy of WARF and Morgridge becomes instructive for early-career scientists like me. The lesson of the last century is that when the “action” restricts science, the “reaction” must pair resources with strategy. Thomson and Steenbock didn’t save their fields by hoping external pressure would pass but rather built new structures to counter them.

I have seen this strategy not just in funding science but in rebuilding trust. According to a 2020 USPTO report, women are named as inventors on only about 13 percent of patent applications despite making up roughly 25 percent of the nation’s STEM workforce. I’ve been fortunate to work with a team at WARF dedicated to understanding these disparities and identifying opportunities to bridge this gap. If we want to counter public skepticism, our institutions must evolve to be more equitable. Resilience today requires widening access to discovery just as much as funding it.

For scientists, the history of Morgridge and WARF show that discovery never moves forward on a frictionless surface — the box will always (and rarely politely) push back. Discovery only advances because people choose to push it forward.