The Morgridge Institute for Research was born from the recognition that basic, curiosity-driven research drives medical progress. Great research institutions need a mechanism to support taking advisable risks on promising but unproven research questions.

At Morgridge, it has grown into what we call “fearless science.”

In 1998, Wisconsin scientist Jamie Thomson successfully isolated stem cells from human embryos, creating not just a new field of science, but a new field of medicine.

The discovery was epic in scope, and the rest of the world would soon respond with aggressive programs to establish their own stem cell research presence.

People recognized that Wisconsin needed to create something transformational that would protect our leadership in this new science and help keep Thomson in Wisconsin.

But stem cell research was controversial in the early days. Thomson’s work could jeopardize federal funding for UW–Madison if his lab remained on campus.

During this same period, a national push was emerging for more interdisciplinary research. The National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation began encouraging universities to find creative ways to spark discovery across disciplines.

Thanks to the support of visionary leaders, Wisconsin was able to address both of these challenges with a single initiative.

A partnership emerges

In 2004, Governor Jim Doyle committed $50 million for a new building if the university could provide matching funds. This was part of Wisconsin’s BioStar initiative to dramatically upgrade science research facilities across the state.

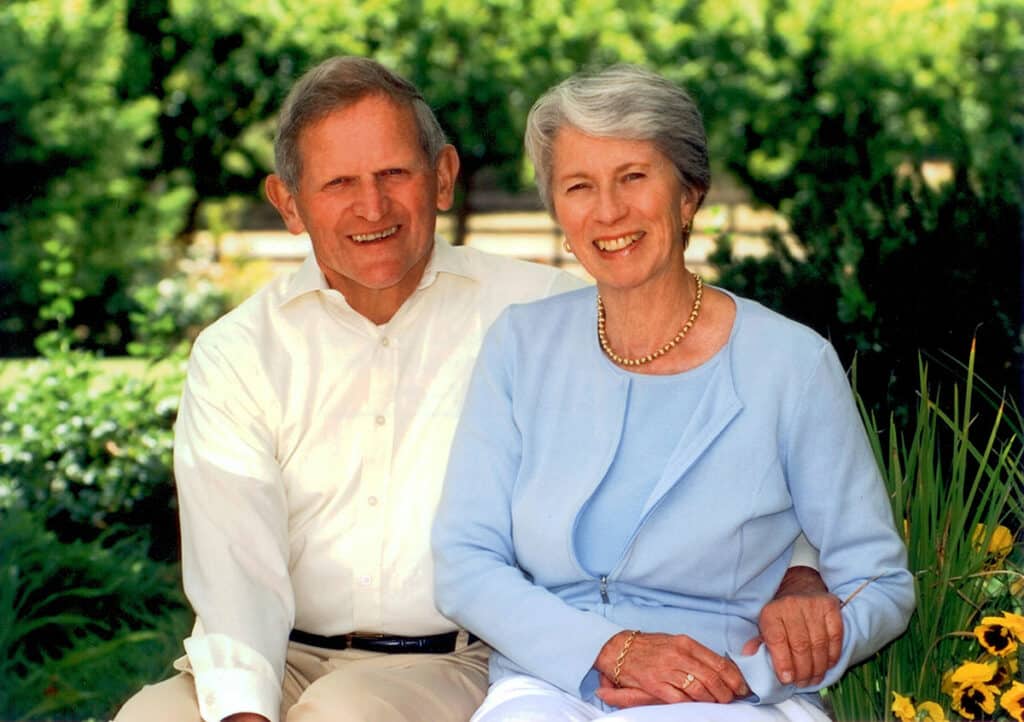

UW–Madison alumnae John and Tashia Morgridge agreed to be an early financial partner to ensure this unique and valuable research building would come to fruition. John, a trustee of Stanford University, had seen the impact of the Clark Center and BioX program there and wanted to bring the independent institute model to the Midwest.

At the same time, the project became a three-way partnership when the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) agreed to be an additional investment partner. WARF, which manages the technology and innovation coming from university researchers, exists to promote, encourage, and aid scientific investigation at UW–Madison.

Both the Morgridges and the WARF board emphasized that a private institute would bring a flexibility and nimbleness to research, something the university can’t always provide because of state policies and oversight.

They wanted to create a place willing to take risks and press against boundaries. To help create future science that we can’t currently imagine.

As an independent institute, we have the freedom to move quickly and decisively, to follow interesting and important questions, wherever they may lead.

Yet they gave us the best of both worlds. We are also deeply engaged with a world-class public university, with state-of-the-art tools at our disposal and access to partnerships with every department of the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

We have a strong, collaborative relationship with the chancellor and with the medical school, and all of our research themes were born from extensive input from the campus research community.

Engaging science and society

WARF also provided pivotal support for the robust science programming activities developed for the Discovery Building’s public first floor — often called the “campus living room.” Ever since we opened our doors in 2009, outreach to schools and communities has been integral to our work. Inspired by Tashia Morgridge and her passion for education, we use our unique space to engage the public in the joy of science.

Our deeply symbiotic relationship with WARF and the university has helped us attract and keep the best possible talent by offering joint UW-Morgridge appointments. Most Morgridge investigators have faculty appointments and enjoy all the benefits that come with faculty status.

Our approach to new discoveries has also led to strategic investments at key moments that served as a catalyst for new research directions. Together with the university, we are leaders in cryo-electron microscopy and mass spectrometry technologies and our research computing capabilities can address today’s massive data science challenges in biology.

None of this would have been possible without the vision of John and Tashia Morgridge and the WARF board around the turn of the century. They remain involved in the Morgridge Institute because we are an important avenue to ensure the university remains competitive. And because our science remains fearless.